By Stephen O’Connor

Expecting a tidal wave of distressed selling and recapitalizations at 30-50% discounts to pre-COVID values, the private equity industry raised an unprecedented amount of capital in the early months of the pandemic. Fund after fund reported breathlessly the size of their newest, distressed real estate offering and the ease and speed with which they attracted capital. In Q2 of 2020, new funds dedicated to real estate investing raised $45.5 billion, the largest second quarter amount in each of the past five years and 24.4% higher than the $36.5 billion raised in Q2 2019.

However, since then, other than some creative structured financings by the likes of Starwood Capital, Angelo-Gordon, Oaktree, MSD Capital and Ramsfield, there have been surprisingly few institutional-quality, distressed real estate closings. The lament throughout P/E land is that sellers have an unrealistic sense of value and that lenders are not forcing a day of reckoning. What the heck happened?

The answer is multi-dimensional:

- First, there are few “bad guys” in this crisis. Delinquent borrowers are generally trying their best to deal with an unprecedented situation and lenders have been inclined to work with borrowers rather than punish them.

- Second, Dodd-Frank successfully forced the banking industry to reduce leverage, maintain greater liquidity and limit their holdings of complex financial instruments. As a result, the banking industry entered the crisis in an unprecedented state of fiscal strength, which gave banks the financial capacity to be more flexible with borrowers.

- Third, banks recognized, especially in the early months of the pandemic, that the negative press likely to accompany foreclosure actions would be intense and wisely elected not to repeat their PR mistakes during the Great Recession.

- Finally, critically, lenders were unwilling to step into the chain of title in situations where they would be writing checks every month to cover operating losses and would also be vulnerable to lawsuits from guests and workers exposed to COVID.

It is our view that, with the vaccines being rolled out, lenders will continue to “kick the can” and the window to buy truly distressed assets will rapidly close. That doesn’t mean that there won’t be good deals available, but the opportunity to buy quality hotel properties at steep discounts will disappear more quickly than anyone imagined. Instead, beginning late in the second quarter and extending through the rest of 2021, we believe we will see a large number of recapitalizations, and quite a few sales, by “motivated” owners (as opposed to “distressed sellers”) at valuation levels generally in the range of a 10-25% discount to 2019 levels.

With banks and securitized lenders relegated to the sidelines in the hospitality market because of their pesky requirement for trailing cashflow to support their underwriting, the debt funds should have a heyday for the next 12-18 months.

The tidal wave that was looming on the horizon in the summer of 2020 will reach the beach as a large, but comfortably surfable, wave this summer.

The One-Eyed Man is King

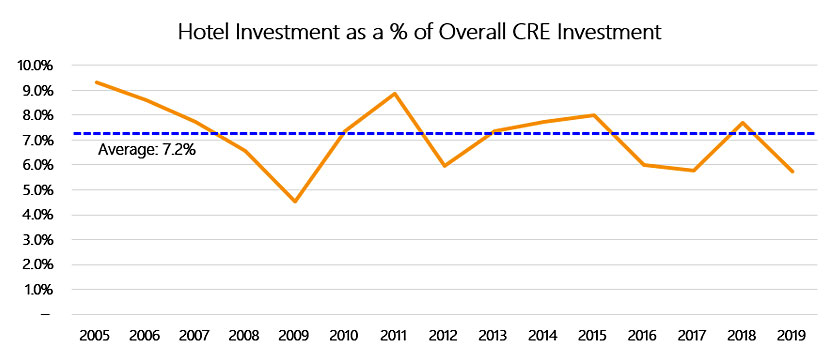

Most institutional investors view hotels as a niche investment class and place fairly strict limits on their hotel exposure. That viewpoint makes sense when one considers the relatively small size of the hotel market, the operating complexities of lodging properties, the daily “mark-to-market” on room rates and the cyclical nature of the industry. Interestingly, we believe that this cycle could be different and that hospitality assets will comprise a much larger share of most institutional portfolios, especially those of private equity funds and large family offices, and for a more sustained period than we’ve seen in past recoveries.

The reason for this change is less a function of something good happening in the hotel industry than it is of secular changes in other classes of commercial real estate. Specifically, when one looks at the four major classes of commercial real estate (office, multi-family, retail and industrial/warehouse), office and retail are severely challenged by the complex, still-evolving changes in demand for those assets, while multi-family and industrial/warehouse have seen prices soar powered by low interest rates and a Niagara Falls of equity capital. Put more simply: office investment is a conundrum, everything but grocery-anchored retail is toxic, multi-family is overpriced and warehouse/distribution is wildly overpriced.

That leaves hotels as one of the only CRE classes where (i) assets can be acquired at a discount to long-term value, (ii) there is a reasonable expectation that demand will (eventually) return to historical levels, and (iii) valuations are expected to recover to pre-COVID levels.

Stephen O’Connor is a principal and managing director of RobertDouglas

This is a contributed piece to Hotel Business, authored by an industry professional. The thoughts expressed are the perspective of the bylined individual.